Table of Contents

1. Introduction

The Common Hill Myna (Gracula religiosa) is a member of the starling family Sturnidae and is a common resident of Singapore’s primary and secondary forests[1]. It is one of the nine members of Sturnidae in Singapore and should not be confused with the Javan Myna (Acridotheres javanicus), Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis) and Crested Myna (Acridotheres cristatallus). Despite its common status in Singapore[1] and large geographical range (approximately 3,880,000 km2), its numbers in other regions that the species occupies are declining due to widespread trapping for the pet bird trade for its renowned ability to imitate human speech and everyday sounds (Video 1).[1],[2]

Video 1. Common Hill Myna singing and talking (Source: YouTube)

This species page aims to provide useful information, be it the general descriptions, interesting behaviours, and taxonomy details, for anyone who wishes to learn about the Common Hill Myna. An overview of this page's information can be seen through the Table of Contents. The different page sections would appeal towards different visitors to this page:

If you are a birder: Description and Diagnosis

If you are an undergraduate or high school student: Distribution and Biology

If you are a conservationist: Impacts of Human Activities

If you are interested in the species' phylogeny and taxonomic status: Taxonomy

If you really want to learn more about the Common Hill Myna: Every section is interesting!

If you find that the certain sections of this page is "trimmed off" due to alignment and screen resolution issues, the print version (More Options > Print) will be a better alternative.

You are welcome to post any constructive comments and feedback by clicking the comment icon on the top right hand corner of this page.

2. Etymology

The Common Hill Myna and other hill myna species are commonly known as Grackles and thus their generic name "Gracula" is derived from the Latin word "Graculus", also known as a Jackdaw. The Common Hill Myna's specific name "religiosa" could have been due to the old practice of teaching captive Common Hill Mynas to utter short prayers, particularly in Bengal[3].

3. Description

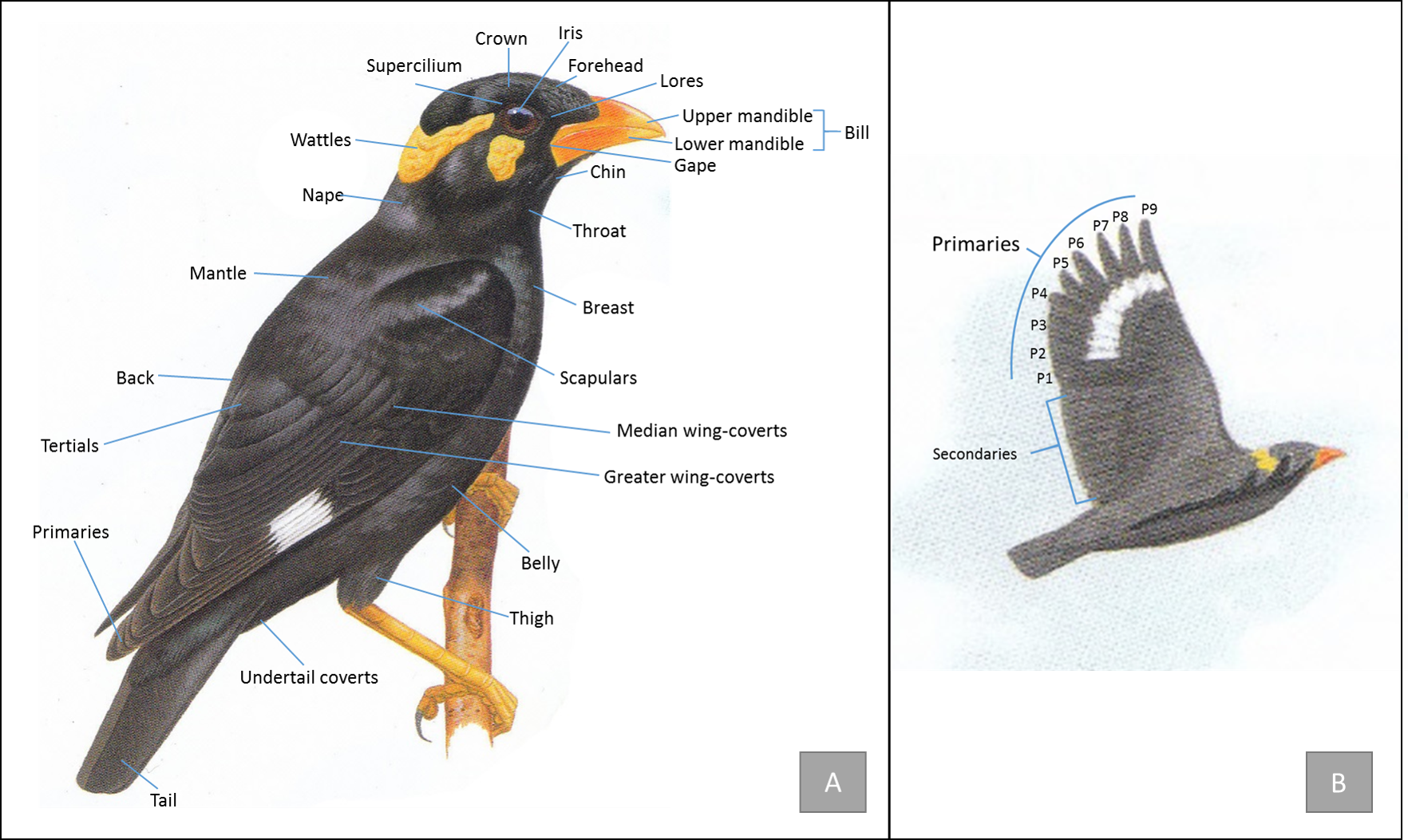

(Images are from: Starlings and Mynas, Feare & Craig, 1999 - Direct permission not obtained but within the limits of Fair Use)

3.1 General Field Identification of Common Hill Myna

The following information provides useful field identification details that one should take note of when trying to identify a Common Hill Myna. The Common Hill Myna is a stocky glossy black myna that is about 28 to 30 cm in length. Both genders have similar physical appearances[4].| Head |

Sides and back of head bears bright yellow skin and wattles. Arrangement of wattles varies between subspecies |

| Central crown, nape, mantle, breast |

Bears black feathers that are glossed purple |

| Sides of face |

Velvety black feathers |

| Rest of the body |

Bears black feathers that are glossed greenish |

| Primaries |

Central part of primaries are white, forming a conspicuous broad white band in flight |

| Bill |

Orange, sometimes reddish with a yellow tip |

| Legs and feet |

Large and chrome yellow in colour |

| Iris |

Dark brown |

| Tail |

Black, short and square |

Call

Recognizing the vocalizations of different bird species is essential in providing details about the location and identification of the birds. The Common Hill Myna has a distinct single, repeated piercing whistle: “HEE-ow, HEE-ow, HEE-ow” (pers. obs.). Listen to its call in the bottom audio player (Audio 1)!

Audio 1: Call of Gracula religiosa in Koh Phangan, Thailand (Source: xeno-canto, Author: Vladimir Yu. Arkhipov, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND License)

For information regarding the calls of Gracula religiosa, please refer to Section 6.5 Calls.

Average Measurements[5]

| Male |

Female |

|

| Weight |

250 g |

230 g |

| Wing length |

177 mm |

174 mm |

| Tail length |

82.75 mm |

81.6 mm |

3.2 Description of Gracula religiosa subspecies

(Most information is derived from Feare & Craig 1999[4]. Images of head features, where available, are obtained from Wikimedia Commons, Author: Shyamal, Creative Commons BY-SA License[6])| Subspecies(with head features) |

Skin patches and wattles |

Head |

Body |

Wings |

Bills |

G. r. religiosa |

|

|

|

|

|

| G. r. batuensis (Head image unavailable) |

|

|

|

|

|

G. r. palawanensis |

|

|

|

|

|

| G r. venerata (Head image unavailable) |

|

|

|

|

|

G. r. intermedia |

|

|

|

|

|

G. r. peninsularis |

|

|

|

|

|

G. r. andamanensis |

|

|

|

|

|

4. Diagnosis

The Common Hill Myna looks very similar to its other sister species of hill mynas (Genus Gracula). However, these sister species are mostly endemic to certain areas and by paying attention to their head features (e.g. Wattles and bill), it is still possible to tell them apart from one another.| Species |

Head Features[6] |

General Description(with location details[7]) |

|

|

Location: Moist forests from Indian east to southern China, Indochina, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia east to Alor, Palawan (Philippines) Length: 28 to 30 cm Description:

|

Nias Hill Myna (Gracula robusta) |

|

Location: Hill forest of Nias and Banyak Islands, off western Sumatra. Length: 30 to 36 cm Description:

|

Sri Lanka Myna (Gracula ptilogenys) |

|

Location: Humid forest of southwestern Sri Lanka Length: 23 to 25 cm Description:

|

|

|

Location: Endemic to Enggano Island off southwest Sumatra. Length: 27 cm Description:

|

Southern Hill Myna (Gracula indica) |

|

Location: Moist hill forests of southwestern India and southern Sri Lanka. Length: 23 to 24 cm Description:

Audio 2. Call of Gracula indica (Source: xeno-canto, Author: Stuart Fisher, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND License) |

)

)Now that you are familiar with the diagnostic features of the Common Hill Myna, test your knowledge with this short game below!

Due to its common name, the Common Hill Myna, this species is also confused with two other myna species that are much more common in Singapore. The following are pictures of the Javan Myna and Common Myna for your reference.

5. Distribution

5.1 Global Distribution

Common Hill Mynas have a wide naturally occurring range that extends from the forests of India and eastwards through Burma, Thailand and Indochina[7]. They are found in southern China, Hainan and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Their range further extends southwards to Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, Borneo and the Palawan Islands of the Philippines[12].Common Hill Mynas have also been introduced and established populations in Florida, Puerto Rico and Hawaii. This is likely due to the prevalent trade of these birds as popular cage birds[12].

The following map displays the generalized distribution of the Common Hill Myna and also shows the distribution of its subspecies and other species of the genus Gracula. You can view these distributions by toggling between the three map layers provided (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Generalized distribution of the Common Hill Myna, with its subspecies and other species belong to Genus Gracula. Information about this distribution is obtained from: Starlings and Mynas (Feare & Craig, 1999) & xeno-canto

5.2 Distribution in Singapore

In Singapore, Common Hill Mynas are located at Bukit Batok Nature Park, Bukit Timah Nature Reserve, Central Catchment Nature Reserve, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin, Singapore Botanic Gardens, St John's Island (Figure 5)[8].Figure 5. Distribution of the Common Hill Myna in Singapore. Information about this distribution is obtained from: The DNA of Singapore, RMBR

6. Biology

6.1 Habitat

In Singapore, Common Hill Mynas are recorded in primary and secondary forests, forest edge and occasionally scrubs[1].

(Photo from Flickr, User budak, Creative Commons BY-NC-ND License)

In general, they are typically found in areas of high rainfall and humidity, especially in the edge of moist evergreen or semi-green forest[4],[9]. Sometimes, they also occur in wet deciduous forest. They are most commonly found in hills between 300 and 2000 m, but do occur in sea level, such as in Singapore. The mynas inhabits dense jungle but are more commonly found and noticeable at the forest edges, thinned areas and clearings[3]. These species can also be found in among large flowering trees that are cultivated in tea and coffee plantations (e.g. In the Lesser Sundas). They have been recorded in mangroves as well[4].

Common Hill Mynas are not known to be migratory but were observed to have regular seasonal movements (more wandering especially in the winter) and move between different altitudes depending on nest site availability and food availability, which is much reduced in the winter[3].

6.2 Diet

Common Hill Mynas are mainly frugivorous but they do feed on nectar, insects and other animals. They consume mainly Ficus fruits and also berries and seeds from a wide variety of trees and shrubs. Several fruits are quickly swallowed one after another and their seeds will be regurgitated soon after. These birds are thus useful seed dispersers for fruiting tree species.They were observed to consume floral nectar from Salmalia, Bombax, Erythrina, Grevillea and the forest shrub Helicteres isora, thus making them suitable cross pollinators as well. Common Hill Mynas feed on insects by mainly gleaning them off the foliage of trees, searching on large branches, within bark crevices and amongst creeper tangles and clumps. They also join flocks of other bird species to feed on swarms of winged ants and termites in the air[3].Their young are commonly fed with lizards and insects[3],[4],[10]. Lizards are possibly considered to be a delicacy among the birds as they were observed to be chasing one another to feed on a lizard prey. Betram (1970)[3]observed the birds manipulating lizards by carrying the prey between their beaks and "thwacked violently and repeatedly against" their perch, before swallowing whole and feeding it to their young[3].

In Singapore, an individual myna was observed holding an egg between its mandibles, postulating the likelihood of this species to develop a nest raiding behaviour. However, such behaviour has not been observed nor recorded and thus it is unlikely that this species raids nests[11]. If you like to see pictures of this strange sighting, please visit this article HERE.

Common Hill Mynas are commonly observed drinking water from tree holes and may also drink water from the ground[3].

6.3 Behaviour

Common Hill Mynas usually occur in pairs and do occur in large groups of 10 to 12 individuals during the non-breeding seasons, but can occasionally gather up to groups of 50 individuals[4],[10]. They tend to congregate at fruiting trees and pairs are apparent in such flocks. No aggression is displayed to conspecifics and several pairs may even nest in the same tree. Neighbouring nests are commonly found about 1 km apart. Bertram (1970)[3]observed that when "a breeding pair which sees or hears another pair within its range usually flies at once to join them; the two pairs perch close together, call frequently, and fairly soon disperse; no aggression is detectable in such cases, and the 'owners' may sit and preen in a leisurely manner close to the newcomers."[3] The mynas roost either in pairs or in family groups on leafy branches or in tree holes. Prior to roosting, the birds display more vocalization from high perches on the trees. Common Hill Mynas are almost strictly arboreal and tend to perch on top of exposed dead branches (Figure 7)[4].

Their flight is rapid and direct (Figure 8), commonly flying at speeds of about 30 km/h and occasionally exceeding this speed. They usually fly in an undulating woodpecker-fashion when one member of a pair chases another. While flying, it was observed that the birds' wings produced a "loud musical humming noise" that are presumed to assist in flock cohesion. As mentioned previously, the white wing watch is only obvious in flight and could thus serve as an indication to maintain contact between the flocking birds and to stimulate other perching individuals to fly[3].

Bertram (1970)[3]made an interesting observation of the birds' behavior shortly before they fly:

"Mynahs frequently stretch their wings, in one or both of two ways: either, with the bird standing on one leg, the wing is extended downwards past the other outstretched leg; or, squatting on the perch, the bird raises both wings above its back. In both cases, the wing patches are displayed maximally to birds nearby; this wing-stretching, and the associated displaying of a flight signal, may be undergoing ritualization as a take-off signal."[3]

In trees, the birds move along the branches by hopping sideways. They also hop, instead of walking, along the ground, which is rarely observed[4]. The birds have been observed to bathe in water-filled holes found in trees or on the ground. They were also seen to occasionally dew-bathe among foliage and bathing in light rain[3].

Comfort behaviour among pairs have been observed, where the birds practice allopreening on each other[12]. If you wish to see pictures of this behaviour, please visit this article HERE.

6.4 Breeding

The breeding seasons of the Common Hill Mynas varies depending on where they are located in the region. For example, G. r. intermedia is found in the northern region of Thailand and breeds mostly during February and April, whereas the southern Thailand race, G. r. religiosa, breeds later during April to June[10]. Bertram (1970)[3]observed that females adopt a horizontal (but not crouched) posture, raising and quivering their tail up and down rapidly to solicit copulation from males[3].Nest characteristics

Common Hill Mynas are monogamous and pair for life. During the breeding season, the birds are commonly seen in pairs and nest at the bottom of deep cavities that are at least 10 m high in tall trees[4]. As the birds are non-excavating, these cavities are usually created either by other species of excavating birds or from holes created by fallen branches or fungus. Larger subspecies, such as G. r. religiosa, nests in cavities with larger entrances and shallower depths. Previous observations have shown that if the selected nests have small entrances[4], the birds are often observed to squeeze themselves through the entrance! According to Archawaranon (2003)[10], the northern birds of Thailand often nested in various forest types, such as hill evergreen and mixed deciduous forests, and the southern birds nesting only in rainforests[10].Nest building

Within the tree cavity, both parents stack sticks and leaves obtained from either the nest tree or nearby trees and forms a rough cup-shaped nest (about 4 to 5 cm thick) at the bottom of the cavity[10]. This nest building activity would last about 7 to 11 days, where both parents gather nest materials together but will take turns to enter the cavity[4]. It was observed that “when one bird was inside working on the nest, the other perched vigilantly on a branch very close to the entrance waiting for its partner to come out and then eagerly entered the cavity”.[10]Egg-laying and Clutch size

The clutch size ranges from 1 to 3 eggs[4],[10] and the egg sizes within a clutch varies with the sequence of laying, the first egg often being larger than the third. One egg is laid per day and its colour is turquoise blue with variable brown spots and blotches (Figure 9). The total egg laying period lasts between 3 to 5 days, where the males would perch on a tree stem closest to the cavity entrance. When the female emerges, she will perch near her mate and preens herself with his assistance[10].

Egg Incubation

Both parents take turns to enter the nest and incubate the eggs[4],[10]. Incubation was thought to begin once the first egg is laid. Females were observed to spend more time incubating the eggs and having more incubation shifts than the males. At night, one parent always remained in the cavity with the eggs while the other is found near the entrance. During the day, both parents would leave the nest to forage and came back together. Sometimes they returned with fresh green leaves to add to the nest, possibly to adjust humidity or to avoid disease and ectoparasite infection. The incubation period often lasts between 14 to 17 days[10].Nestlings

Once the eggs have hatched, the parents would remove the egg shells but leave unhatched eggs in the nest. Both parents feed their nestlings mostly by regurgitation or with food between their bills, such as small fruits, insects or lizards. The nestlings are fed by one parent at a time, usually in the morning and evening. Parents will remove faecal sacs and place them on a nearby branch. After 25 to 28 days, the young are fully fledged and leave the nest quickly before their parents return to start a new clutch[10].6.5 Calls

Many calls of the Common Hill Myna are low-pitched and human-like[13]. In the wild, the birds have been observed to mimic the calls of other conspecifics but they do not mimic the calls of other species or animals, although it is a widely held misconception that they do (Video 2)[4].Video 2. Common Hill Myna calls (Source: YouTube)

For more information about the calls displayed in this video, please read the article found HERE.

The species has a wide range of calls that are classified into four distinct categories of vocalisation by Betram (1970)[3]:

- "Chip-calls": Loud, piercing, short and descending squeaks made by all adults when alarmed or when communicating with each other from a distance. The call is observed to be made with an open bill (Figure 10) and jerking movements of the body.

- "Um-sounds": Soft grunts that are made when individuals are in close range with each other

- "Whisper-whistles": Soft high-pitched noises made by inactive birds and are unique to each individual

- "Calls": Includes a huge variety of whistles, croaks, wails and shrieks when the birds see or hear one another

If you like to hear even more amazing calls of the Common Hill Myna, do visit this page HERE.

Bertram (1970)[3]also observed captive Common Hill Mynas to study the vocal development of newly hatched mynas until they become adults. Newly hatched mynas beg their parents for food by making "high-pitched squeaking sounds". As they grow older, these begging calls become louder lower-pitched trillings. Even after the young are fully fledged, they continue to make such begging calls especially when they encounter an adult that has food between its bills. Such food begging calls usually disappear within a week and are replaced by soft juvenile squawks that are made in situations similar to the "um-sounds" made by adults. After a fortnight after fledging, the juveniles made a variety of squawks, squeaks and harsh sounds as an action known as "chortling". These sounds are produced softly and continuously, becoming louder with age. As the juveniles grow into adults, these chortle sounds disappear and the birds adopt the typical adult calls[3].

7. Taxonomy

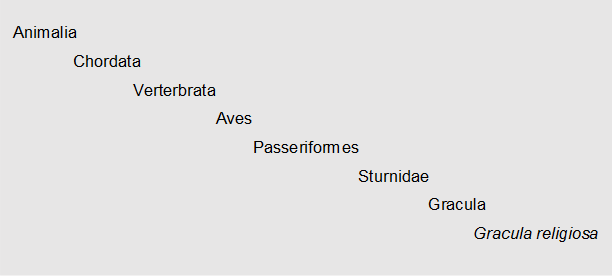

7.1 Taxonavigation

The ranks of the following taxonavigation have been removed as they do not provide additional information to the classification of Gracula religiosa[15].

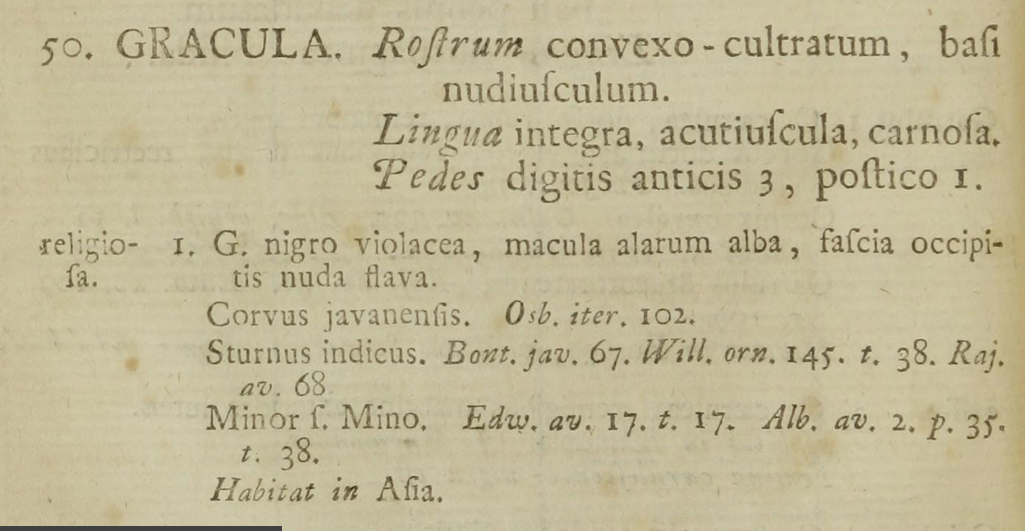

7.2 Type Specimen

The type specimen is found in the National Museum of Natural History, Naturalis, in Leiden, Netherlands[16]. It was described by Carl Linnaeus in 1758 (Figure 11)[17].

(Scanned document from the Biodiversity Heritage Library)

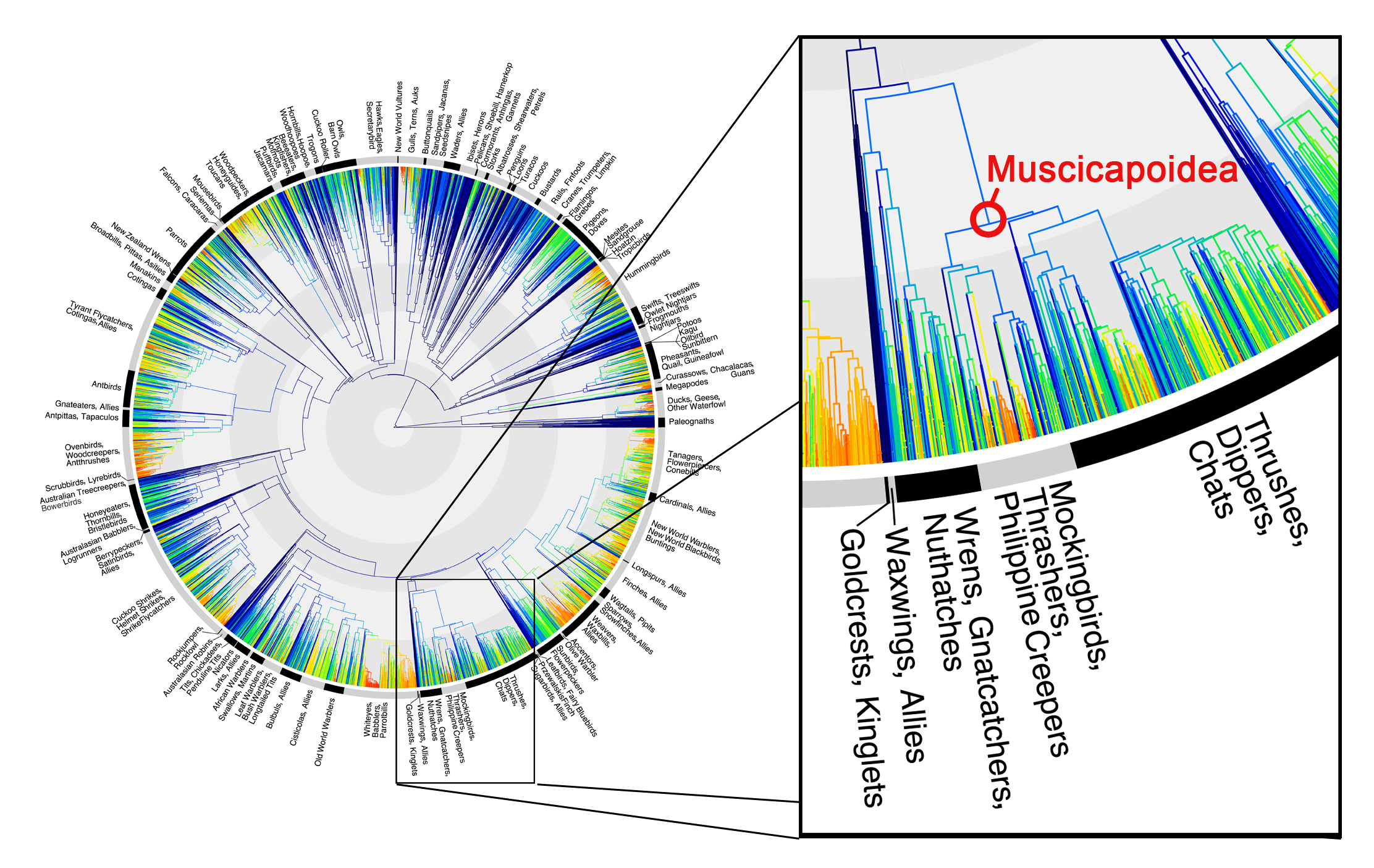

7.3 Phylogenetics

Common Hill Mynas belong to the family Sturnidae, which is part of the Muscicapoidea that is composed of the large diversity of Old World songbirds[18]. From Jetz et al 2012’s complete dated phylogeny of birds, the age of the Muscicapoidea clade is approximately 38.8 million years old (Figure 12)[20]. Within the Muscicapoidea clade, a few phylogeny studies have been done to examine the relationships among its members.[18],[21],[22]

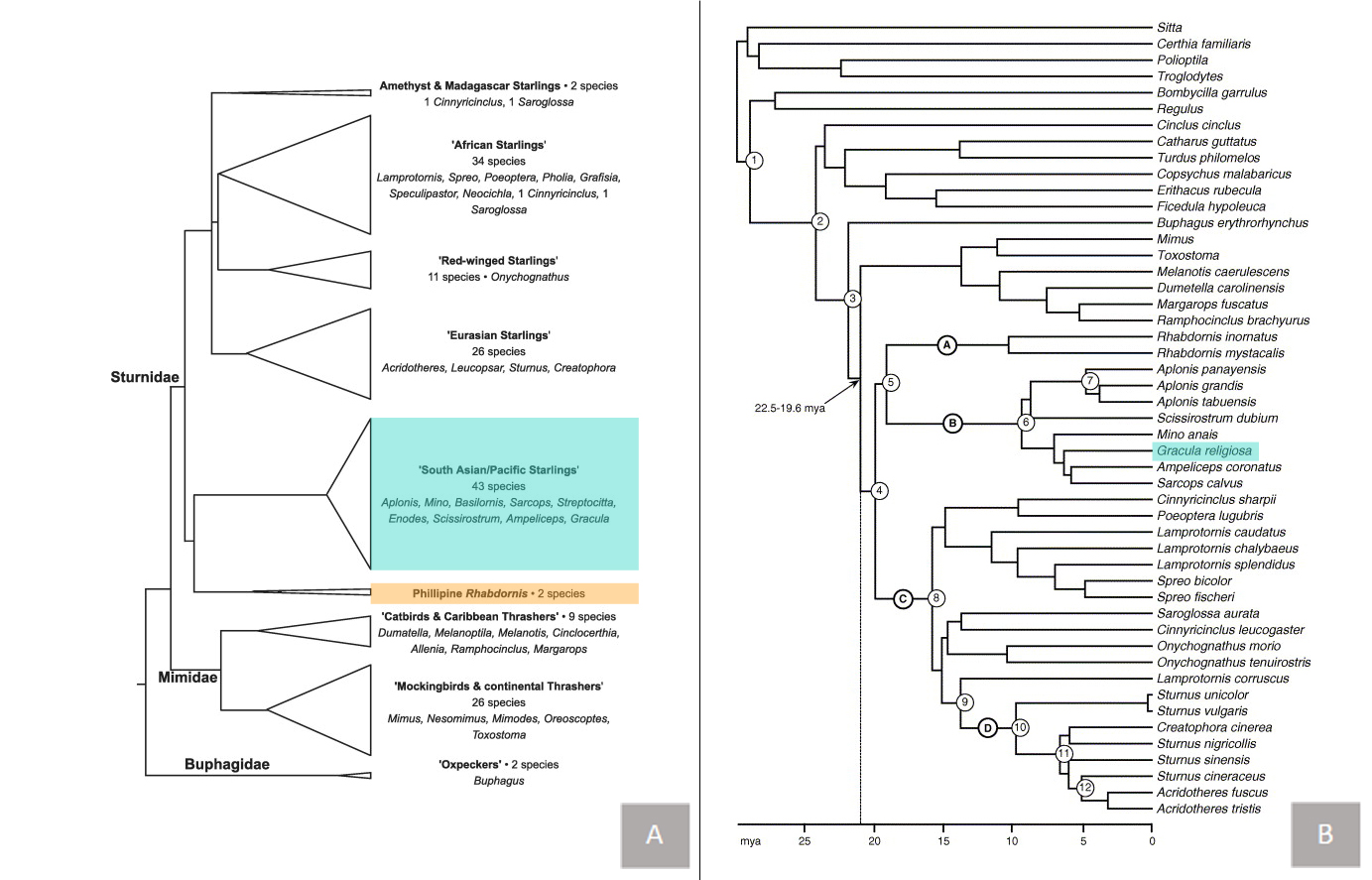

The Muscicapoidea are composed of three main groups: (1) the Cinclidae (dippers), (2) the Muscicapidae sensu lato (thrushes and Old World flycatchers), and (3) the Sturnidae sensu lato (starlings and mimids, including Buphagus and Rhabdornis), in which Common Hill Mynas belong to[18]. Within the Sturnidae are six major subclades: (1) Amethyst & Madagascar Starlings, (2) ‘African Starlings’, (3) ‘Red-winged Starlings’, (4) ‘Eurasian Starlings’, (5) ‘South Asian/Pacific Starlings’ and (6) Philippine Rhabdornis (Figure 11A)[21]. Using nuclear sequences from the RAG-1 gene, Cibois and Cracraft (2004) suggested a sister group relationship between the ‘South Asian Starlings’ and the Philippine Rhabdornis lineages[18]. This relationship, however, did not show enough statistical support, as noted by Zuccon et al. (2006)[20].

This relationship was confirmed by both Zuccon et al 2006 and Lovette & Rubenstein 2007, through further analyses on gene sequences (Zuccon et al 2006: Two nuclear,RAG-1 and myoglobin, and one mitochondrial gene; Lovette & Rubenstein 2007: Combination of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences)[20],[21]. The ‘South Asian Starlings’ clade consists of a large diversity of species that are found in India, Southeast Asia and various archipelagos in the Indo-pacific[21]. It includes arboreal and frugivorous species, such as species from the genera Aplonis, Gracula, Ampeliceps, Mino[20],[21]. Zuccon et al. (2006) suggested that “this lineage includes surviving species of an old radiation which occurred in and near the Wallacea region”. They presumed that one lineage diversified in the South East Asia and split early (18 mya) into the Philippine endemic Rhabdornis (Figure 13B, Clade A) and Clade B (Figure 13B) that include Gracula and related genera[20].

Their hypothesis is opposed by Lovettle & Rubenstein (2007), who instead suggested that this group has only undergone a very recent period of explosive diversification, sharing a more recent common ancestor than any other speciose clade within the entire radiation. Its large diversity of this group perhaps due to ecological release, rather than a relictual retention of ancient differentiation as suggested by Zuccon et al (2006)[20],[21].

For a more visual representation, watch this video and to see where the Common Hill Myna is located on OneZoom's Tree of Bird Life!

Video 3. Common Hill Myna's position on OneZoom's Tree of Bird Life. (Source: Screencasted using Screenr from OneZoom, Creative Commons BY-SA License)

7.4 Subspecies

Seven subspecies of the Common Hill Myna are recognized under two checklists of global birds, namely the IOC World Bird List[22] and the Clements Checklist of Birds of the World[23].| Subspecies |

Author(s) |

Locality (according to IOC List) |

Locality (according to Clements Checklist) |

| G. r. religiosa |

Linnæus, 1758 |

Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Borneo and nearby islands |

Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, Bali, Borneo and Bangka Islands |

| G. r. batuensis |

Finsch, 1899 |

Batu and Mentawai Islands (Off West Sumatra) |

Batu and Mentawai Islands (Off West Sumatra) |

| G. r. palawanensis |

(Sharpe, 1890) |

Palawan (West Philippines) |

Palawan (southwest Philippines) |

| G. r. venerata |

Bonaparte, 1850 |

Lombok to Alor (Lesser Sundas) |

West Lesser Sundas (Sumbawa, Flores, Pantar, Lomblen and Alor) |

| G. r. intermedia |

Hay, 1845 |

North India to South China, Indochina and Thailand |

North India to Myanmar, Thailand, Indochina and South China |

| G. r. peninsularis |

Whistler & Kinnear, 1933 |

East Central India |

Northeast peninsular India |

| G. r. andamanensis |

(Beaven, 1867) |

Coco, Andaman and Nicobar islands |

Andaman and Nicobar islands |

An eight subspecies, G. r. halibrecta Oberholser 1926, is perhaps distinct (but not valid) from G. r. andamansis, where it is endemic to the Great Nicobar islands and G. r. andamansis to the Andaman Islands[4],[24],[25]. It was described having “two large lappets on the back of the neck, joined together at the top.”[4] Majumdar (1978) suggested that G. r. intermedia could be synonymous with G. r. peninsularis, with G. r. intermedia taking precedence[26].

For information regarding the description of these seven subspecies, please refer to Section 3.2.

8. Impacts of Human Activities

Human activities have a significant effect on Common Hill Mynas in the two main aspects of habitat loss and pet trade[3].8.1 Habitat Loss

As mentioned previously, Common Hill Mynas have a large dependence on a forested habitats to have sufficient food supply and suitable nesting sites. In India, large areas of forests are cleared to make way for cultivation activities and for timber and firewood. The hill people of northeast India are known to practice “jhum”, also known as shifting cultivation (Figure 14), whereby they cut, burn off, plant, reap and subsequently abandon hillside forest areas. This results in the rapid destruction and extensive erosion of the forest, causing a huge loss in suitable habitat for the birds[3]. This species is still able to tolerant a certain degree of habitat loss. However, the decline of populations in various regions is accelerated when the impacts of pet trade occur in conjunction with habitat degradation[27].

8.2 Pet Trade

Common Hill Mynas are popular cagebirds (Figure 15) due to their ability in mimicking human speech and everyday sounds very well[2]. This species rarely breeds in captivity and hence, large numbers have been captured from the wild[3],[10]. The CITES (2006)[2]report estimate up to over 170,000 individuals exported from its range States of Bangladesh, Bhutan, Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, India, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Thailand[2]. Capture methods vary across different area, depending on the local practices and the birds’ age[3]. The species is heavily traded across Asia and exported mainly via Malaysia and Singapore to the United States of America, Japan and Europe, particularly to Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Italy and France[2].

In south India, the birds (mainly G. r. indica) are captured as adults during the non-breeding season, where they occur in large flocks and are trapped using bird lime, an adhesive substance used to trap birds, that is applied on flowering or fruiting bushes. In northeast India, the birds are caught using bird lime-coated sticks placed on the top of seasonally fruiting trees. This method of capture was originally created by the Naga hill people to consume the Common Hill Mynas as a curried bird delicacy[3],[4]. In the Garo Hills of Assam, India, the birds breed in artificial nest sites, made of basket nets tied onto a bamboo framework and tied to the top of trees. Young nestlings (about 3 weeks old) are collected and contribute to half of the exported birds from northeast India. The other half are collected from natural tree cavities from Orissa and Nepal. Together with the impacts of habitat loss, the Common Hill Myna population in northeast India have declined considerably[3].

The high demand for this species have considerable impacts on its breeding success in Thailand. Archawaranon’s (2003)[10]study demonstrated that out of the 88% of birds that did not manage to fledge, 61% were illegally stolen by humans as young nestlings to be traded. When human interference was prevented in the Mae Hong Son and Satun provinces, 75% of eggs hatched managed to fledge successfully[10].

8.3 Conservation

Despite the impact of the above two human activities, the IUCN status of the Common Hill Myna is listed as “Least concern”. This is firstly due to its large geographical range and secondly, its decreasing population trend is not sufficiently rapid to approach the thresholds for "Vulnerable", of which the population trend criterion is a >30% decline over ten years or three generations[27]. Fortunately, the species is protected in some countries, such as Myanmar, Thailand and India, as their wild populations have been severely impacted by the pet trade and habitat loss. India has banned the export of Common Hill Mynas in 1972 but illegal trade of the species still continues[3]. At the request of Thailand, this species was included in CITES Appendix III in 1992 and subsequently in Appendix II in 1997[2].Captive breeding is one alternative to satisfy the human demand for Common Hill Mynas and to decrease human impacts on wild populations. Archarawanon (2005)[28]has demonstrated that captive breeding can be successful when provided with the essential reproduction needs and preventing predation. Captive-bred birds can serve as “a demographic and genetic reservoir” and this method can aid in conserving this species. However, re-introducing these birds requires long term monetary support and commitment to train them before their release, such as to avoid predators, find food, finding and constructing suitable nests, interacting with conspecifics and finding mates. Suitable sites needs to be selected and accessed to ensure successful re-introduction[28].

Thus, a more realistic approach would be use captive bred Common Hill Mynas to supply the pet trade. Captive birds are generally more tamed, imprint on humans easily and are able to express more vocal mimicry of any sound[29]. Labour costs are quite cheap and monetary support is generally for feeding the birds[28].

.

Hope that you have learned much about the Common Hill Myna from this species page!Feel free to visit these sites listed below to gain information not just about the Common Hill Myna but also about birds in general!

9. Useful links

Common Hill Myna related:Common Hill Myna on ADW: http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Gracula_religiosa/

Common Hill Myna on EOL: http://eol.org/pages/922307/overview

Common Hill Myna on Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Hill_Myna

Common Hill Myna on RMBR DNA: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/794

Common Hill Myna on the IUCN Red List: http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/106006841/0

Common Hill Myna on BirdLife International: http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=6841

Birds related:

Bird Ecology Study Group: http://www.besgroup.org

The Cornell Lab of Ornitology: http://www.birds.cornell.edu/Page.aspx?pid=1478

BirdLife International: http://www.birdlife.org/worldwide/science

OneZoom's Tree of Bird Life: http://www.onezoom.org/birds.htm

A Global Phylogeny of Birds: http://birdtree.org/

Xeno-Canto Bird Sounds: http://www.xeno-canto.org/

Oriental Bird Images: http://orientalbirdimages.org/

Birds of Singapore: http://singaporebirds.blogspot.sg/

Birds of NUS: http://nusavifauna.wordpress.com/

For Fun:

Birdorable: http://www.birdorable.com/

Bird and Moon: http://birdandmoon.com/

10. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Eunice Soh for her constructive feedback and help with the problems encounter while creating this species page.

David Tan for his constructive feedback and Common Hill Myna photo.

All researchers, authors and users for their information, photos and videos used in this species page.

All the above information falls under Fair Use. Relevant authors are acknowledged and credited.

Thank You!

11. References

1. Yong, D. L., K. C. Lim, & T. K. Lee, 2013. A Naturalist’s Guide to the Birds of Singapore. John Beaufoy Publishing, Singapore. 134 pp.2. CITES, 2006. Gracula religiosa. From the Twenty-second meeting of the Animals Committee. Lima: Peru, 33 pp.

3. Bertram, 1970. The vocal behaviour of the Indian Hill Myna, Gracula religiosa. Animal Behaviour Monographs. 3(2): 79-192

4. Feare, C. & A. Craig, 1999. Starlings and Mynas. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 143-145 pp.

5. Hoogerwerf, A., 1963. Some subspecies of Gracula religiosa (Linn.) living in Indonesia. Bulletin of the British Ornitologists’ Club. 83: 155-158

6. “Gracula.svg,” by Shyamal. Wikimedia Commons, File:Gracula.svg. URL: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gracula.svg (Accessed on 28 October 2013).

7. Feare, C. & A. Craig, 1999. Starlings and Mynas. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. 66-67 pp.

8. "Gracula religiosa" Retrieved from The DNA of Singapore, Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research. URL: http://rmbr.nus.edu.sg/dna/organisms/details/794 (Accessed on 28 October 2013).

9. Manakadan, R., J. C. Daniel, & N. Bhospale, 2011. Birds of the Indian Subcontinent: A Field Guide. Oxford University Press, New York. 373 pp.

10. Archawaranon, M. 2003. The impact of human interference on Hill Mynahs Gracula religiosa breeding in Thailand. Bird Conservation International. 13: 139-149.]

11. KC Tsang, 26 September 2007. Hill Myna stealing an egg. Bird Ecology Study Group. URL: http://www.besgroup.org/2007/09/26/hill-myna-stealing-an-egg/ (Accessed on 28 October 2013).

12. Daisy O’Neil, 18 July 2012. An encounter with Common Hill-Mynas Part 1. Bird Ecology Study Group. URL: http://www.besgroup.org/2012/07/18/%C2%A9-an-encounter-with-common-hill-mynas-part-1/ (Accessed on 28 October 2013).

13. Sun Chong Hong, 12 February 2011. Songs of the Hill Mynas. Bird Ecology Study Group. URL: http://www.besgroup.org/2011/02/12/songs-of-the-hill-mynas/ (Accessed on 28 October 2013)

14. Wells, D.R., 2007. The birds of the Thai-Malay Peninsular. Vol. II, Passerines. Christopher Helm, London. 800 pp.

15. ITIS, 2013. Gracula religiosa. Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). URL: http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=179652 (Accessed on 28 October 2013)

16. “List of type specimens of Passeriformes (birds, Aves) in the National Museum of Natural History, Naturalis, Leiden” National Museum of Natural History, Naturalis, Leiden. URL: http://lelouxj.home.xs4all.nl/avestypes.html#top (Accessed on 28 October 2013)

17. Linnæus, C. 1758. Systema naturæ per regna tria naturæ, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. 108 pp. Holmiæ. (Salvius)

18. Cibois, A. & J. Cracraft, 2004. Assessing the passerine ‘‘Tapestry’’: phylogenetic relationships of the Muscicapoidea inferred from nuclear DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 32: 264–273.

19. Jetz, W., G. H. Thomas, J. B. Joy, K. Hartmann, & A. O. Mooers, 2012. The global diversity of birds in space and time. Nature. 491: 444-448.

20. Zuccon, D., A. Cibois, E. Pasquesy & P.G.P. Ericson, 2006. Nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data reveal the major lineages of starlings, mynas and related taxa. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 41: 333-344.

21. Lovette, I. J. & D. R. Rubenstein, 2007. A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the starlings (Aves: Sturnidae) and mockingbirds (Aves: Mimidae): Congruent mtDNA and nuclear trees for a cosmopolitan avian radiation. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 44: 1031-1056.

22. Gill, F & D Donsker (Eds), 2013. IOC World Bird List (v 3.5).URL: http://www.worldbirdnames.org [Accessed on 10 November 2013].

23. Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, B.L. Sullivan, C. L. Wood & D. Roberson. 2013. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: Version 6.8. Downloaded from URL:

http://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ (Accessed on 10 November 2013)

24. Abdulali, H., 1967. The birds of the Nicobar Islands, with notes on some Andaman birds. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 46: 704-708.

25. Sankaran, R., 1998. An annotated list of the endemic avifauna of the Nicobar islands. Forktail 13: 17-22

26. Majumbar, N., 1978. On the taxonomic status if the Eastern Ghats Hill Myna, Gracula religiosa peninsularis Whistler and Kinnear, 1933 [Aves: Sturnidae]. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 75:331-333.

27. BirdLife International 2012. Gracula religiosa. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.1. URL: http://www.iucnredlist.org. (Accessed on 10 November 2013.)

28. Archawaranon, M., 2005. Captive Hill Mynah Gracula religiosa breeding success: potential for bird conservation in Thailand? Bird Conservation International. 15:327–335.

29. Archawaranon, M. (2005) Vocal imitation in Hill Mynas. Gracula religiosa: factors affecting competency. International Journal of Zoology Research. 1:26–34.